A new tool for food system transformation

20 December 2021

The Copenhagen Food Accelerator Lab has been busy!

At the Copenhagen Lab, we know that chefs in restaurants and canteens are important actors in the food system, with the power to choose who wins and loses in the game of growing and selling food. Our working theory is, the more chefs know about the impact of their procurement, the better able they are to act as agents for sustainable food system transformation, by sourcing ingredients with a positive impact.

The problem, and perhaps, part of the solution?

Our aim at the Copenhagen Lab is to encourage systemic change in favor of local food system resilience – or in other words, to shorten the chain between farms and eaters, by encouraging food businesses and ordinary citizens to continuously support smaller, less distant agri-food actors. Not only are such actors better able to pivot amid uncertainty, they also offer better transparency, concentrate more value with farmers and makers, and support agrobiodiversity and ecosystem services locally.

Worldwide, people depend more and more on imported foods, arriving to them at the end of longer, and more complex supply chains, when compared to more localized systems. And while the proportion of global food actors’ control over the food system is increasing, the number of these suppliers is actually decreasing (Kummu et. al., 2020). This is one of many indications of the troubling trend of decreasing food system resiliency at the local level. We depend more and more on fewer and fewer large food companies, which due to their size and complexity are more vulnerable to shocks, such as agricultural disruptions due to climate change, and global pandemics, to name a few pertinent examples.

By contrast, smaller agri-food actors with more direct relationships to partners and consumers have demonstrated better ability to pivot amid the Covid-19 pandemic, ensuring we get the food we need. In Denmark, producers such as Birthesminde, marketplaces such as Grønt Marked and Coop Crowdfunding, and subscription-based vendors such as GRIM, and Blue Lobster are a few examples of local actors that adapted quickly in order to fill the gaps created by the pandemic, and make sure Copenhageners not only had safe access to the food they needed, but perhaps to fresher, more nutritious food, with a more direct line to local producers than they might have had before.

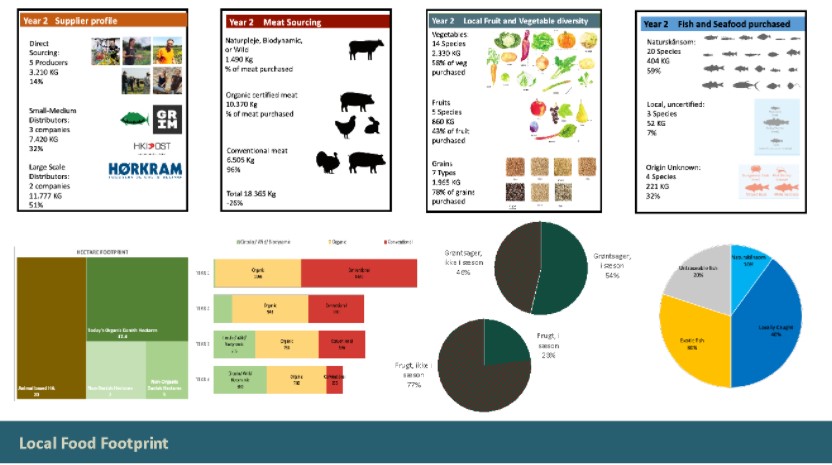

Measuring impacts on the local food system

In response to decreasing food system resilience amid increasing uncertainty, and starting with restaurants and canteens as our initial target user, the Copenhagen Lab has been developing a new tool that shows how much organic Danish farmland supplies participating canteen and restaurant kitchens. Drawing from yield data supplied by Denmark’s Organic Association (kilograms of organic produce per hectare in Denmark), and using procurement data from professional kitchens (kilograms of products purchased), the tool takes the total kilograms of products the kitchen buys, and calculates the approximate number of organic hectares currently supplying the kitchen, as well as the maximum number of Danish, organic hectares the kitchen could be sourcing from, if they were to prioritize local and traceable ingredients when possible. The resulting quantification of local, organic land area can be used as a new metric of success, giving professional kitchens the opportunity to see their current and potential impact on sustainable local agriculture, and work towards a more positive impact on the local foodshed by targeting more local, organic, seasonal, plant-based production through their procurement (figure 1).

Figure 1 – Example of a kitchen’s procurement impact, according to eight measurable indicators, including supplier types, hectares of farmland, meat types and the proportion of meat in kitchen buyings, number and diversity of fruits and vegetables, proportion of ingredients purchased in season, types of fish purchased, and the origin on fish and seafood purchased.

In spring, 2021, after prototyping the tool, we recruited nine Danish canteens – collectively purchasing approximately 6.8 million kg of food ingredients each year – to pilot it and calculate their current and potential organic hectares, and further expand their perception to include other impacts on the local food system. In addition to organic hectares, the analysis introduced additional indicators, such as agricultural biodiversity, seasonality, and the number of steps between the farm and the kitchen.

What we’ve learned (so far)

It turns out that while the picture is indeed complex, knowledge about this complexity is motivating, and helpful in setting goals with impacts that are measurable, and most importantly, relatable when put into a local context. Having calculated the current and potential hectare footprint of the nine pilot kitchens, and explored strategies for shifting towards a healthier and more resilient local food system with them, the chefs and kitchen managers from our pilot kitchens have spoken.

Figure 2 – Presentation of the local hectare indicator to pilot kitchens.

Here are a few highlights from this summer’s focus groups discussions with pilot kitchens:

- Story is everything. Whether it’s the story about a product, how it was produced, or the farmer that it grew it, chefs and eaters alike all want the narrative behind their food to be not only a good one, but a true one as well.

- You can’t win all the time. While some kitchens are doing great in certain areas – for example they source from a high number of organic, local hectares – they may not be doing well in another aspects – for example, their menu may be too heavy on meat and dairy, when compared to the EAT-Lancet Commission’s Planetary Health Diet.

- Knowledge is not the only barrier. While chefs may be inspired to act, given this new way of seeing their impact on the food system, the system in place has created a path-dependency, which hinges on scarce resources, contractual obligations to large wholesalers, and convenience. It will take more than awareness and goal-setting to shift procurement towards more diversity, seasonality, traceability, and equity at the local level.

Applying the insights gathered from professional kitchens in response to the tool, while relying on the latest food system science, we are now busy upgrading this “local food footprint” tool. We hope to empower food actors beyond chefs, such as wholesalers and online marketplaces, who can use the tool to shift the paradigm, and almost single-handedly create an environment within which their customers (including restaurants and canteens) can make informed choices when it comes to sustainable procurement.

Citizens- We need your help too!

As powerful as food businesses may be, however, the utility of a local food footprint calculator isn’t exclusively theirs. Strong and resilient local food systems also need ordinary citizens demanding products with positive social, economic, and environmental impacts at the local level. That’s why in the future, this tool is also meant to empower individuals to understand their own food footprint, and maximize the benefit of their every-day eating.

In order to move forward with tool development, we need to know: what motivates you to choose one food or one product over another? What do you find confusing, conflicting, or perhaps just missing from the information you’re presented with at the supermarket, on food labels, at your canteen, or at your local eatery?

Join FoodShift2030 by making your demands clear at [email protected], and join the Copenhagen Lab’s push for more transparent and resilient food systems.

Photo credit: Marie Sainabou Jeng